Now for the Numbers: Vacant Parishes (II)

20 June 2023

My post last week about the growing number and length of parish vacancies led one reader to forward me some statistical information that is of considerable interest. I thought it was worth a “Part 2” on the subject. My thanks to Colin Reilly for allowing me to reproduce the data which forms the basis of what follows.

For the Australian Church as a whole, the current percentage of parishes without a vicar/rector is 28%. It turns out that Melbourne (24%) is actually doing better than some others. Nonetheless, nationally the past year has seen an increase of around 2.5% in the vacancy rate. The rising percentage is in fact helped along by a statistically significant reduction in the number of parishes nationally over the past twelve months – perhaps a sign that the effects of the pandemic are leading to some tough decisions being made in at least some jurisdictions. The raw number of vacant parishes has grown in the past year, but not as dramatically.

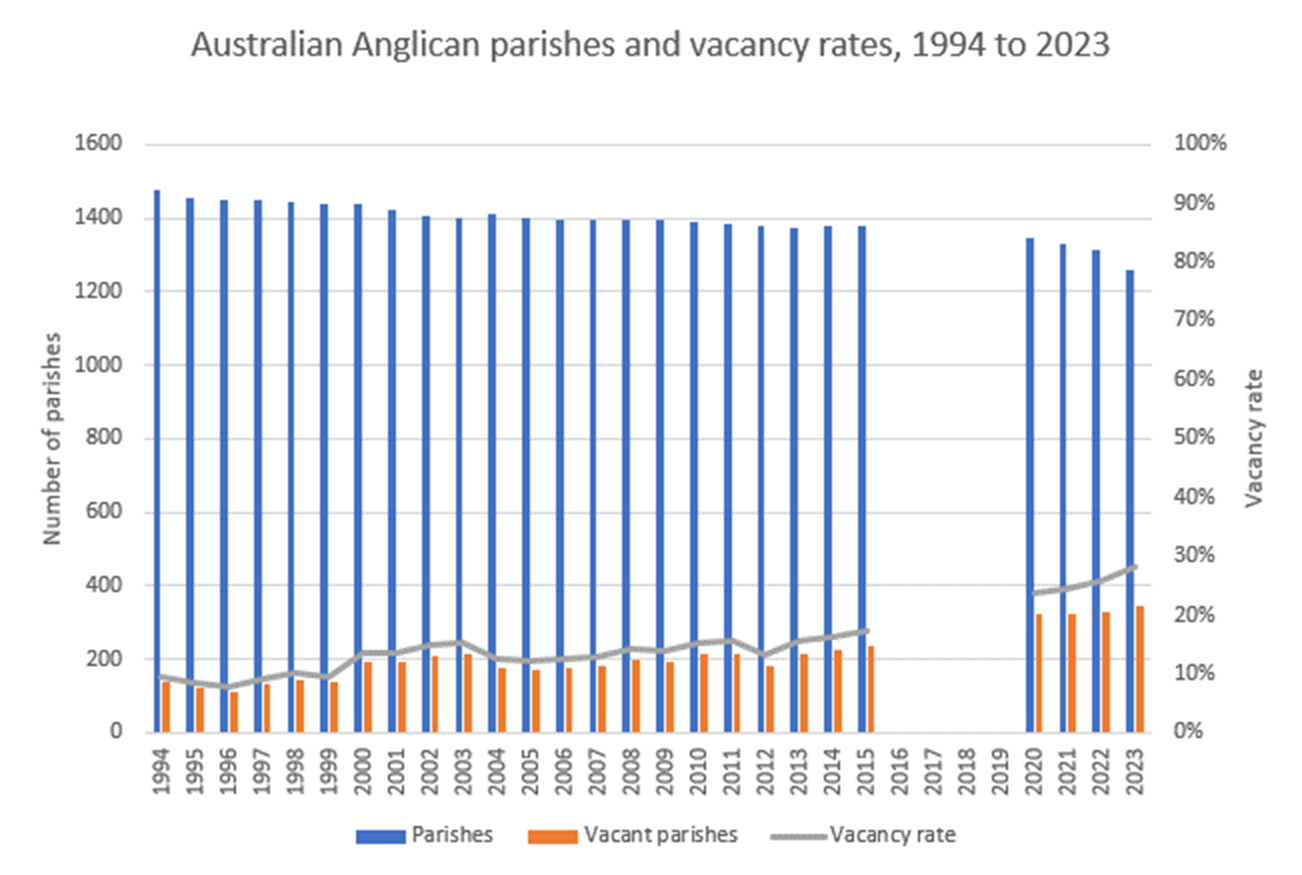

The data reveals that there has been a gradual upward trend in vacancies for at least the past thirty years. It is equally clear that there has been a fairly dramatic acceleration in the past decade (nb. there is no Directory data available for 2016-2019.) In the graph below one can see that even though the number of parishes is declining, the number of vacancies continues to rise both in percentage terms and in raw numbers:

Graph derived from parish lists in the Australian Anglican Directory 1994 to 2015 and the database supporting The Anglican Church of Australia Directory from 2021

In the Covid and post-Covid period, the uplift in vacancies in Melbourne has been even more dramatic than the national average:

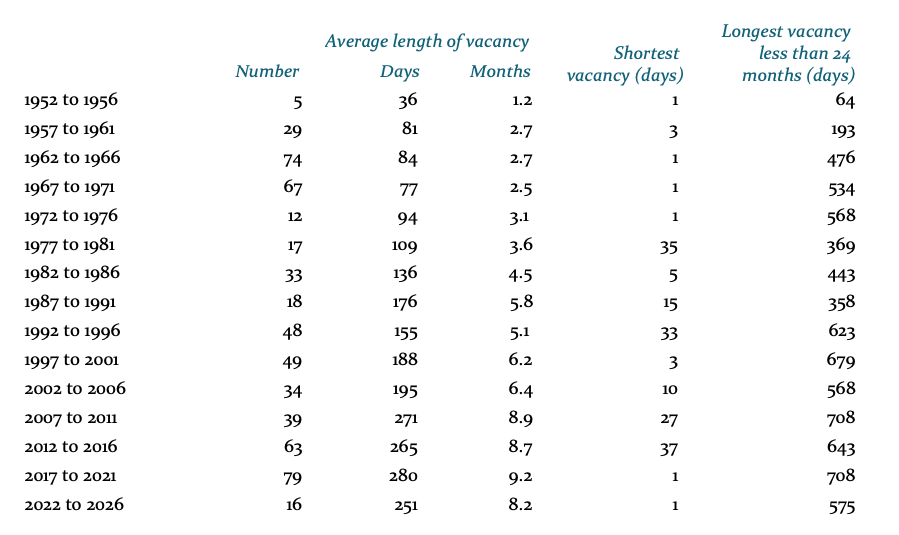

Looking then at the Diocese of Melbourne in isolation, we may add the length of vacancies into the equation. Colin notes that:

· vacancies longer than two years have been excluded from this report as these are usually for particular reasons that would distort the averages shown here.

· Effective vacancies may be longer than is shown here where vicars take outstanding leave between the end of one appointment and beginning the next.

· There are about 150 vacancies in any one five year period. In this report the averages for any period for which more than thirty (20%) vacancies have been reported therefore is likely to be an accurate approximation of the overall experience in that period.

It is now normal in Melbourne for vacancies to last for a year, with an average of almost nine months. (And remember this does not include the time prior to the vacancy formally starting, when the outgoing vicar uses up their remaining leave entitlements.) This compares to an average vacancy period of one month in the 1950s, three months in the 1970s, and six months in the 1990s and early 2000s. If the current trend continues, we may reasonably expect vacancies to average a year in the 2030s.

One of the most important things that the charts and table above demonstrates is that the crisis in parish vacancies has not come about suddenly and is not simply a post-Covid phenomenon (notwithstanding that there has been an acceleration in the Covid and post-Covid period.) It cannot be attributed to any one bishop or policy. This has been decades in the making, and is national in scale. It is the direct outcome of the numerical attendance decline in the church nationwide, and the lack of willingness of those in diocesan leadership to make hard (and unpopular) decisions. The questions I asked at the end of my last post remain valid: “What would it take” to change this state of affairs? For the data suggests we must attempt something. If the current trends continue we may be looking at as many as 35-40% of Australian Anglican parishes without incumbents within a decade, average vacancies of over a year, and many parishes going perhaps for several years without a vicar/rector.

This is not how things ought to be, nor is it a problem without a solution if there is a willingness to make the hard calls. As Colin comments, “If the target was average incumbency length of ten years and average interregnum of 6 months the vacancy rate would be 5%.” In other words, the state of affairs that obtained in the 1960s. To achieve this result would require one or both of two things to happen: increase the supply of parish clergy, or dramatically decrease the number of parishes through amalgamations or church closures. It seems to me, with many parishes hosting tiny congregations, that the latter is the only sensible solution. In other words, to solve the crisis in staffing parish ministry we need to admit that we are already a smaller church.